The Swiss Feldstutzer – Part 3: range tests of the Model 1851 and Buholzer cartridges

In this chapter I will finally shoot the rifle with the recreated service cartridges. Currently I do not have a mold for the Model 1856 bullet, therefore if you have one, and you wish to help the project, please contact me: info@kapszli.hu. Thanks!

Accuracy of the Model 1851 cartridge

The forcing principle did not stand the trial of time that is for sure as it vanished at the end of the 1850s. However the excellent deviation in the muzzle velocity was promising. I was hoping to get remarkable accuracy. I always begin testing the accuracy of the rifle at 50 meters shot from a bench with soft supports under the fore-end and the butt-stock to minimize the errors from the human factor. I fire five shots in a series and measure the group size of the best four as even if the rifle is placed on a shooting rest human errors can have a negative effect.

First group of the Feldstutzer Model 1851 cartridge at 50 m: impact point walking up and left as barrel fouled. The rifle had already 8 shots in the bore that I spared for measuring the muzzle velocity.

Recovered Feldstutzer patches damaged by the fouled bore. Primary reason for inaccuracy.

Te forcing principle makes loading slow and hard and as the black powder fouling builds up in the bore after each shot the job gets harder. The more fouling builds in the bore the highest the gas pressure will be. The cartridge is capable of decent accuracy up to 10 shots. After 10 shots the accuracy dropped rapidly, and the bullets were even keyholing.[1] The point of impact elevated and moved to the left shot by shot. I had to recover the shot patches from the range to understand what was happening. The fouled bore damaged the patches making the symmetric blow of gases at the muzzle impossible. The unstable bullets were extremely inaccurate leaving no excuse for the principle of the patched conical bullet. It is clearly understandable why this principle was replaced only in a few years time:

- slow to load cartridge

- inaccuracy after a few shots

- too many components needed for the construction of the cartridges

My first experiences did not support the remarkable accuracy of the rifle and cartridge praised by the contemporary sources. The group size shown on the first 50 meter experiments were not better than the group of the larger calibre military rifles of the era.

5 shots fired from a clean bore at 50 meters. Not bad, but nothing more than any other muzzle loading military rifle was capable.

0.38 mm lubricated patch and the Model 1851 bullet

Original mold for the Model 1851 bullet

Wild and Wurstemberger was right in the question of the adaptation of the small calibre, but the forcing principle quickly proved to be a dead end in firearms development.

The Model 1856 Jäger rifle

After arming the sharpshooter companies of the Swiss Army with small calibre rifled arms the next step was to arm the light infantry of Jäger companies of the infantry battalions as well. The new Model 1856 Jägergewehr was a close descendant of the Model 1851 Feldstutzer. It had a 93 cm long bore with as slightly smaller 10.35 mm calibre. The bore had 5 grooves and lands. The twist rate of the rifling was 810 mm.[2] The rifle lacked the set trigger system and the Schützen-type stock. The form of the butt plate was straight just as on other contemporary military rifles. The rear sight was the same but the mounting method of the bayonet was a socket style rather than the steel mounting sleeve attached to the bore of the Model 1851 rifles.[3] A new bullet and new cartridge construction was introduced with the new rifle. The deadline for the purchase of the complete batch of new rifles was the end of 1860.

The Model 1856 cartridge

The introduction of the compression bullet designed by Robert Merian[4] also meant a significant change in the cartridge construction and marked the end of Wild’s forcing principle. The new bullet for the Model 1856 Jäger rifles was 23 mm long, had a diameter of 10.10 mm and weighted 16.62 g. The bullet was loaded into the bore with the greased paper patching of the paper case. The case itself was rolled on a wooden mandrel. The trapezoid inner layer held the powder while the rectangular outer layer held the lubrication. According to the official regulation for the Jäger rifles the cartridge was manufactured from writing paper and the lube applied to the part of the case holding the bullet was mixed from 1 part beeswax and 5 parts of tallow. [5]

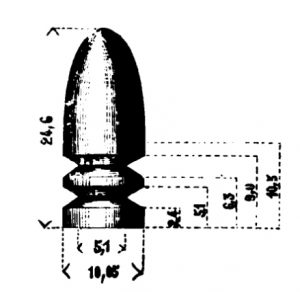

The Model 1856 bullet

The caps were pressed from brass sheet and the exploding compound was a mix of mercury-fulminate and saltpetre. It was water proofed with a layer of varnish. 10 cartridges were packed in a paper wrapping including 14 caps separated by 7-7 in smaller paper cases.[6]

This system was a close copy of the cartridges used by the French, British and Austrian army, and this construction was already in use with the larger calibre Swiss rifles. The paper patched bullet had many advantage compared to the cloth patched bullet. First of all it was easier to load. The bullet went down the bore with the weight of the ramrod without necessary force from the soldier. Second the paper separated the lead bullet from the bore preventing leading of the rifling. Lead deposit in the bore had a negative effect on accuracy. The charge of the cartridge was 4 g of “Flintenpulver”[7] that was an equivalent of Nr. 3. powder (1.2 mm corn diameter so it was a finer powder than used for the Model 1851 rifles)[8]. The muzzle velocity of the Model 1856 cartridge fired from the Model 1856 Jägergewehr was 470 m/s.[9]

The first compression bullet was introduced with the new Model 1856 rifle for the Jägers but in 1859 it was accepted in a bit modified form for the Model 1851 Feldstutzer rifles also. The new bullet had a flat base, two compression grooves, 10.05 mm diameter, weighing 16.6 g. This bullet was technically the scaled down copy of the Austrian Lorenz bullet.[10] This bullet was not cast by the soldiers anymore but supplied to the troops from central warehouses. A good indication of this change in logistics is the absence of the bullet mould an access lead from the cartridge box of the Jäger soldier.[11]

The new cartridge had a dramatic impact on the rate of fire. It was easier and faster to load so the soldier was able to reach the rate of fire of 2-3 rounds per minute, just as any other military muzzle loading rifle of the era.

Recreating the Model 1856 cartridge

The paper quality of the outer envelope plays an important part in recreating the cartridge. The durability and thickness of the paper are key elements in reproducing the original accuracy. The paper patching wrapped the bullet in double layers. The cartridge must be loaded easily in the bore so the diameter of the paper patched bullet cannot be larger than the land to land diameter of the bore. The gap between bullet and bore is: 10.5 – 10.05 = 0.45 mm. This value must be divided by 4 to arrive to the thickness of the paper sheet: 0.1125 mm. The paper must of a strong material ensuring that it will not separate from the bullet while loading only after it left the muzzle.

The No. 3. powder in grain sizes equals to the modern made Swiss black powder No. 4. Based on the experiences with the Model 1851 cartridge the equivalent load of 4 g of the modern made powder can be accepted in this case as well. The muzzle velocity of the original cartridge was 470 m/s.[12]

Accuracy of the Model 1856 cartridge

Unfortunately I was not able to get hold of a mould that drops bullets for this cartridge. If you happen to have one, or you can send me bullets for the tests, please contact me.

Small calibre or large calibre? Arming the Swiss infantry with small calibre rifles.

The Buholzer bullet

Even if the advantages of the small calibre were obvious it was still not clear whether the complete infantry should be armed with such firearms. On 31 January 1860 the Bundesrath established an expert commission to investigate the best calibre for all the infantry rifles to be adopted in the future. The clear winner of these tests was a 12.8 mm calibre rifle designed by Mr. Burry and Mr. Buholzer in Lucerne. Based on the experiments the commission proposed 12 to 12.6 mm or 12.9 to 13.5 mm to be the new caliber of all rifles, with a chance to include the Feldstutzers also. The new barrel length to be adopted for the larger calibre was 99 cm. In the meantime Buholzer was working on a new bullet also to match the new bores. He designed a skirted Minié-style long bullet and created several samples for smaller calibres also. The official tests in 1862 proved that the new bullet design works perfectly with the already adopted Jäger rifles also, so the discussion regarding the calibre question turned immediately resulting the full acceptance of the small calibre. [13] The new rifle entered service under the designation Model 1863 Linien-Gewehr. It was a close descendant of the Model 1856 Jägergewehr with a 99 cm long cast steel barrel, 10.4 mm calibre, 5 grooves rifling, and 1:810 mm twist rate.[14]

On 7th January 1863 the Bundesrath issued a memorandum to the Federal Assembly in support of the small calibre stating another important aspect of having a lighter bullet. This reason was probably the strongest of all: saving money. Making a Buholzer bullet needed 46% less lead than it was used for the old large calibre infantry rifles. This was exceptionally important as regular target practice was a key element of establishing the fighting power of the Swiss battalions.[15]

Rearming the complete Swiss Federal Army needed a huge investment. Altogether 80.064 rifles were to be purchased at a price of 80 Franks, altogether 6.405.120 Franks as total expense.[16] Each rifle was to be equipped with 160 cartridges adding another 534.444 Franks to the grand total.[17]

The Buholzer bullet and cartridge

The Buholzer cartridge

In 1863 the new cartridge was adopted for the Model 1851 Feldstutzers, Model 1856 Jäger rifles and for the new Model 1863 Infantry rifles as well. The cartridge itself was of a very simple construction. The inner powder sleeve was made of a 40 mm wide, 67 mm long rectangle of thin carton paper glued and folded. The outer envelope was made of very thin but very strong paper. It was a trapezoid form. Length: 124 mm, height: 68 and 38 mm. The lubed paper wrapping covered the projectile in two layers.[18] The diameter of the bullet was: 10.2 mm, length: 26.71 mm, weight: 18.25 g, length of the complete cartridge was 85 mm. The black powder charge was 4.1 g.[19]

Recreating the Buholzer cartridge

Te 4.1 g charge was measured by weight from Swiss No. 5. black powder. The paper for rolling the cartridge was 0.08 mm thick to completely fill the gap between the bore and bullet (10.5 mm – 10.2 mm = 0.3 mm, divided by 4 = 0.075 mm). The bullet was cast from a reproduction mold that dropped 10.5 mm bullets. These bullets were sized to the desired 10.2 mm diameter. The paper sheets added another important information to the quality of the contemporary powders: even if the granulation of the modern made Swiss powder is close to the ones used in the 19th century the weight by volume is different. My cartridges measured only 75 mm in length, 10 mm less than the originals. This proved that the volume of 4.1 g powder was larger in the 19th century than now.

My recreated Buholzer cartridge: one opened to show inside

Reproduction mold for the Buholzer bullets

Paper sheets ready for cartridge rolling.

The powder column is not only shorter in the cartridge but of course in the barrel’s powder chamber also. The “Wild” disc on the ramrod prevented pushing the bullet to the powder so instead of having 0.4 mm gap between powder and bullet in reality it was 15-17 mm in my rifle. This is not acceptable as air gaps can cause excessive pressures damaging the bore. Therefore I decided to skip using the original ramrod and push the bullet firmly on the powder to not leave any air gap.

My cartridges were shorter than the originals showing the difference of the powder’s weight/volume

The Buholzer cartridge is very easy to load. It goes down the bore with the weight of the ramrod speeding up the loading process. The bullet and powder are united in one paper case so he soldier did not have to reach for the separated bullet in the cartouche. The Minié-style skirted bullet also has an advantage in cleaning the bore. The expanding bullet skirt cleans a portion of the residue of the previous shots aiding to maintain a constant level of fouling in the bore.

The muzzle velocity of the bullets were nearly the same as in the case of the Model 1851 cartridge. The deviancy of the velocity was a bit larger but it was still in the acceptable range.

| 4.00 g No. 5. | Velocity |

| 1st | 449 m/s |

| 2nd | 455 m/s |

| 3rd | 438 m/s |

| 4th | 447 m/s |

| 5th | 448 m/s |

| Average | 447.4 m/s |

| Deviation | 17 m/s |

| Energy | 1852 J |

In fact the heavier Buholzer bullet seemed to utilize the energy of the powder better than the patched conical bullet resulting a higher muzzle energy. The point of impact was 5 cm lower than of the Model 1851 cartridge but to determinate the external ballistics further tests will have to be carried out later.

Accuracy of the Buholzer cartridge

Excellent. What more can I say. The first groups shot at 50 meters from a bench were more than promising. That rifle at this distance with this cartridge puts each bullet in the same hole. The rifle at this short distance is up to modern standards, only the first shot fired from a clean bore was out of the group. 3 shots hit the same hole and the 4th hit only 2 cm below the triple impact.

Remarkable accuracy of the Buholzer cartridge. Up to modern standards.

This cartridge will be the one to be used in the later long range tests.

Shooting the rifle to 50 meters is an important step but cannot tell enough about the real capabilities of the small calibre muzzle loading rifle therefore these test shootings must be continued to larger distances as well in the future. The Buholzer cartridge reproduction proved that it worth carrying on with the range tests.

The impact of the Feldstutzer on infantry tactics

The Feldstutzer, or to be more precise, the small calibre rifled bore loaded with a conical bullet, had a great impact on the theory of shooting and firearms development but it did not effect the tactical use of the muzzle loading rifle. The flat trajectory and increased effective range can lead to the false recognition that the Swiss sharpshooter equipped with the Model 1851 rifle was now dangerous to the enemy soldier at 600-800 meters. I doubt this as a military historian and as a target shooter as well. From tactical point of view the outer limit of hitting an individual soldier is not more than 300 meters. This limit is not set by the capabilities of the bullet. It can be accurate and lethal beyond this distance as well. The limit in the system is the open sight. If you have ever shot with open sights to larger distance than 200 meters you will understand my point. The enemy individual soldier just disappears in the notch of the rear sight. It is very hard to aim properly on such a small target.

My Model 1851 Feldstutzer with Buholzer cartridges ready to (rock ‘n) roll.

It is also very important to understand the purpose of light infantry in the mid 19th century. Sharpshooters, Jägers, voltigeurs and other organized light infantry troops were usually selected from the line infantry. They received the same training as the line infantry but with more emphasis on fighting in open order. The closed order tactical formations of the line infantry were the deployed line, attack column (or the masse) and the square. These formations had to be supported with troops fighting in open order therefore a skirmish line was deployed 200-300 paces in front of the closed ranks. The most important duty of the skirmish line was to prepare the situation for the attack of the closed ranks. Of course the light troops were more suitable for picket duty, reconnaissance, but still they were to be fighting the battle in support of the line infantry. Skirmishing duty required more accurate firearms and more training in target shooting but this does not mean that the sharpshooters on skirmish duty were sniping enemy foot soldiers at distances more than 300 meters, or horse soldier at a distance beyond 400 meters.

So why on Earth had the Feldstutzer sights that could be elevated to 1000 paces (750 m)? The answer is simple. The role of the long range fire was to attack enemy closed formations with large target surface not individual soldiers. This does not mean that a well trained Swiss sharpshooter using the benefits of the terrain was not a formidable battle implement and could not snipe the enemy from larger distances. But this sniper duty could not turn the tide of a 19th century battle. Let us now cite one of the great military theorists of the mid 19th century. Antoine de Henri Jomini summarized his point is his work The Art of War:

“From all these discussions we may draw the following conclusions, viz. :—

- That the improvements in fire-arms will not introduce any important change in the manner of taking troops into battle, but that it would be useful to introduce into the tactics of infantry the formation of columns by companies, and to have a numerous body of good riflemen or skirmishers, and to exercise the troops considerably in firing. Those armies which have whole regiments of light infantry may distribute them through the different brigades; but it would be preferable to detail sharp-shooters alternately in each company as they are needed, which would be practicable when the troops are accustomed to firing: by this plan the light infantry regiments could be employed in the line with the others; and should the number of sharp-shooters taken from the companies be at any time insufficient, they could be reinforced by a battalion of light infantry to each division.

- That if Wellington’s system of deployed lines and musketry-fire be excellent for the defence, it would be difficult ever to employ it in an attack upon an enemy in position.

- That, in spite of the improvements of firearms, two armies in a battle will not pass the day in firing at each other from a distance: it will always be necessary for one of them to advance to the attack of the other.

- That, as this advance is necessary, success will depend, as formerly, upon the most skilful manoeuvring according to the principles of grand tactics, which consist in this, viz.: in knowing how to direct the great mass of the troops at the proper moment upon the decisive point of the battle-field, and in employing for this purpose the simultaneous action of the three arms.

- That it would be difficult to add much to what has been said on this subject in Chapters IV. and V. ; and that it would be unreasonable to define by regulation an absolute system of formation for battle.

- That victory may with much certainty be expected by the party taking the offensive when the general in command possesses the talent of taking his troops into action in good order and of boldly attacking the enemy, adopting the system of formation best adapted to the ground, to the spirit and quality of his troops, and to his own character.”

Was Jomini right in 1838 when writing his work stating that the rifled arms will not revolutionize tactics? Yes he was. He clearly foresaw that the adaptation of rifling itself will not be able to make a significant change in tactics. With the slow rate of fire and the complicated loading methods the bayonet charge will always be necessary. But he did not foresee that due to the fast development of firearms the killing power of the rifle fire will increase dramatically. He did not foresee that the introduction of the breech loading rifles will soon wipe out all he closed formations from the battlefield.

Nor the small calibre nor the rifling, neither the Fledstutzer therefore did not revolutionize infantry tactics but it did contribute a lot to firearms development and marksmanship. To revolutionize traditional infantry tactics the breech loading and later the breech loading repeating rifle was necessary and to give a real value to the role of the sniper the development of rifle optics was essential.

Balázs Németh. 2018.

Part 1: The Model 1851 Feldstutzer and its impact on rifle development – Part 1

Part 2.: The Swiss Feldstutzer – Part 2: recreating the Model 1851 cartridge

Part 3: The M 1856 and M 1863 cartridges and range tests of the Feldstutzer

Part 4: Shooting the Feldstutzer to 100-300 meters

Part 5: Terminal ballistics of the Buholzer cartridge

Books, studies, articles:

Allgemeine deutsche Militair- und Marine-Beitung (DMMB)

Anonymous: Das Deutsche Wehr- und Schützenwesen. Darmstadt, Leipzig, 1862.

Antoine de Henri Jomini: The Art of War. Philadelphia, 1862.

Beroaldo-Bianchini, Natale: Abhandlung über die Feuer- und Seitengewehre, worin die Erzeugung, der Zweck und der Gebrauch aller einzelnen Bestandtheile, dann aller Gattungen kleiner und Jagdgewehre, mit der Angabe und… Wien, 1829.

C. v. H.: Schiesspulver und Feuerwaffen. Leipzig, 1866.

Caesar Rüstow: Das Minié-Gewehr. Berlin, 1855.

Caesar Rüstow: Die neueren gezogenen Infanteriegewehre. Darmstadt, Leipzig, 1862.

Cadmus Marcellus Wilcox: Rifles and Rifle Practice: An Elementary Treatise Upon the Theory of Rifle. New York, 1859.

Dr. Reinhold Günther: Allgemeine Geschichte der Handfeuerwaffen. Leipzig, 1909.

Ernst Hostettler: Hand- und Faustfeuerwaffen der Schweizer Armee von 1842 bis heute. Zürich, 1987.

Friedrich Engels: The history of the rifle. in: Engels as a military critic. University of Manchester, 1952.

Friedrich Müller: Waffenlehre vorzugweise für Gebrauche für Infanterie- und Cavallerie Offiziere. Wien, 1859.

Hans-Dieter Götz: Militärgewehre und Pistole der deutschen Staaten 1800-1870. Stuttgart, 1978.

Hugo Schneider, Michael am Rhyn: Bewaffnung und Ausrüstung der Schweizer Armee – Eidgenossische Handfeuerwaffen. Zürich, 1979.

Johannes Wild: Über Stutzer oder Büchsen. Zürich, 1844.

Josef Schmölzl: Ergänzungs-Waffenlehre. München, 1851.

Julius Schön: Das gezogene Infanterie-Gewehr. Dresden, 1855.

KA, MKSM: Österreichischen Staatsarchive, Kriegsarchiv, Militärkanzlei Seiner Majestät

Karl Theodor Sauer: Grundriss der Waffenlehre. München, 1869.

Rudolf Schmidt: Allgemeine Waffenkunde für Infanterie. Bern, 1888.

Allgemeine Schweizerische Militär-Zeitung (SMZ)

Wilhelm von Ploennies: Neue Studien über die gezogene Feuerwaffe der Infanterie, 2. band. Darmstadt & Leipzig, 1862.

Regulations, manuals, laws:

Beschluss des Schweizerischen Bundesrathes betreffend die Bewaffnung und Ausrüstung der Scharfschützen. 1850. in: Sammlung der in kraft bestehenden Gesetz. 1860. p246-264

Militär-Reglement für die Schweizerische Eidgenössenschaft. Zürich, 1846.

Reglement über die Bekleidung, Bewaffnung und Ausrüstung des Bundesheeres. Zürich, 1852.

Bundesgesetz über die Bekleidung, Bewaffnung und Ausrüstung des Bundesheeres. 1851.

Auszug aus dem Reglement hinsichtlich der Eigenschaften, welche bei der Auswahl der Mannschaft (Infanterie) für jede Waffengattung zu beachten sind, vom 20. Heumonat 1843. in Sammlung der in kraft bestehenden Gesetz. 1860. p371-373

Bundesbeschluss betreffend die Einführung des neuen Jägergewehrs (vom 25. Herbstmonat 1856.) in: Sammlung der in kraft bestehenden Gesetz. 1860. p264-266

Verordung über die Beschaffenheit der Gewehre und Ausrüstung der Bataillons-Büchsenschmied-Werkzeugkisten und der Gewehrbestandtheilkisten, so wie über die Verfertigung und Verpackung der Munition. (Vom 1. Herbstmonat 1859.) in: Sammlung der in kraft bestehenden Gesetz. 1860. p267-294

Onine resources:

Swiss Cartridge Collectors: http://www.ch-munition.ch/

Shooting the Feldstutzer today: http://www.schiferli.net/The%20Swiss%20Feldstutzer%20M51.htm

Swiss Rifles bulletin board: https://www.tapatalk.com/groups/theswissriflesdotcommessageboard/

Swiss Muzzle Loading Shooters Association: http://www.vsv-schuetzen.ch

Verein Schweizer Armeemuseum: https://www.armeemuseum.ch

Swiss black powder: http://www.blackpowder.ch

Colonel Rubin’s ammo collection: https://www.armeemuseum.ch/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Sammlung-Rubin.pdf

Footnotes

[1] The bullet hits the target sideway.

[2] 2 Swiss Fuß and 7 Zoll

[3] Verordung über die Beschaffenheit der Gewehre und Ausrüstung der Bataillons-Büchsenschmied-Werkzeugkisten und der Gewehrbestandtheilkisten, so wie über die Verfertigung und Verpackung der Munition. (Vom 1. Herbstmonat 1859.) in: Sammlung der in kraft bestehenden Gesetz. 1860. p268-269

[4] Robert Merian: 1820-1891, Swiss army officer, member of the Military Collegium of Basel

[5] Bundesbeschluß, betreffend die Einführung des neuen Jägergewehrs. (Vom 25. Herbstmonat 1856.) in: Sammlung der in kraft bestehenden Gesetz. 1860. p264-294 According to the Verordung über die Beschaffenheit der Gewehre und Ausrüstung der Bataillons-Büchsenschmied-

Werkzeugkisten und der Gewehrbestandtheilkisten, so wie über die Verfertigung und Verpackung der Munition. (Vom 16. Herbstmonat 1859.) in: Sammlung der in kraft bestehenden Gesetz. 1860. p285 it was a mix of 1 part wax and 5 parts of tallow.

[6] Verordung über die Beschaffenheit der Gewehre und Ausrüstung der Bataillons-Büchsenschmied-

Werkzeugkisten und der Gewehrbestandtheilkisten, so wie über die Verfertigung und Verpackung der Munition. (Vom 16. Herbstmonat 1859.) in: Sammlung der in kraft bestehenden Gesetz. 1860. p285-286

[7] Wilhelm von Ploennies: Neue Studien über die gezogene Feuerwaffe der Infanterie, 2. band. Darmstadt & Leipzig, 1862. p63-64

[8] Verordung über die Beschaffenheit der Gewehre und Ausrüstung der Bataillons-Büchsenschmied-

Werkzeugkisten und der Gewehrbestandtheilkisten, so wie über die Verfertigung und Verpackung der Munition. (Vom 16. Herbstmonat 1859.) in: Sammlung der in kraft bestehenden Gesetz. 1860. p283

[9] Anonymous: Das Deutsche Wehr- und Schützenwesen. Darmstadt, Leipzig, 1862. p63

[10] Wilhelm von Ploennies: Neue Studien über die gezogene Feuerwaffe der Infanterie, 2. band. Darmstadt & Leipzig, 1862. p179 fig. 54 According to colonel Rubin the weight of the bullet was 15.8 g.

[11] Verordung über die Beschaffenheit der Gewehre und Ausrüstung der Bataillons-Büchsenschmied-

Werkzeugkisten und der Gewehrbestandtheilkisten, so wie über die Verfertigung und Verpackung der Munition. (Vom 16. Herbstmonat 1859.) in: Sammlung der in kraft bestehenden Gesetz. 1860. p271

[12] According to colonel Rubin the muzzle velocity of the Model 1856 cartridge was 430 m/s. Muzzle velocity is not just depending ont he blackpowder charge but also on the length of the barrel. Rubin did not indicate exactly from wich rifle was the cartridge shot from for measuring the velocity. The difference between 470 and 430 m/s can easily be explained by barrel length difference between the Feldstutzer and Jägergewehr.

[13] Wilhelm von Ploennies: Neue Studien über die gezogene Feuerwaffe der Infanterie, 2. band. Darmstadt & Leipzig, 1862. p181-185

[14] Wilhelm von Ploennies: Neue Studien über die gezogene Feuerwaffe der Infanterie, 2. band. Darmstadt & Leipzig, 1862. p183

[15] Wilhelm von Ploennies: Neue Studien über die gezogene Feuerwaffe der Infanterie, 2. band. Darmstadt & Leipzig, 1862. p198

[16] Wilhelm von Ploennies: Neue Studien über die gezogene Feuerwaffe der Infanterie, 2. band. Darmstadt & Leipzig, 1862. p200

[17] Wilhelm von Ploennies: Neue Studien über die gezogene Feuerwaffe der Infanterie, 2. band. Darmstadt & Leipzig, 1862. p200

[18] Wilhelm von Ploennies: Neue Studien über die gezogene Feuerwaffe der Infanterie, 2. band. Darmstadt & Leipzig, 1862. p185

[19]Wilhelm von Ploennies: Neue Studien über die gezogene Feuerwaffe der Infanterie, 2. band. Darmstadt & Leipzig, 1862. p184

I am still wondering where did you get this Buholzer replica Mould – is there any manufacturer that would be able to fabricate one as per provided dimensions?

HI, it is a custom made mold owned by a friend of mine. I know that Volmer also manufactured molds like this.